|

|

|

|

|

The

Status of the Nearshore Live Fish Fishery

and the Need for Effective

Management

|

|

|

|

|

Black

and yellow rockfish (©Don

Gotshall)

|

|

Status of

Fishing

Fish populations within the Monterey

Bay National Marine Sanctuary remain

healthy. The El Niño and La

Niña phenomena of the last two

years have influenced the migration

patterns of some species of fishes, but

the stocks in general are still abundant.

An exception would be some rockfish

stocks, which are healthy but appear to be

somewhat depressed at this time.

Probably one of the most unusual

occurrences this past year was the

appearance of bluefin tuna within

Sanctuary waters; some were even caught in

Monterey Bay.

This year most of the squid in Monterey

Bay have gone into deep water and cannot

be reached by the commercial fishermen's

nets. Bluefin tuna caught in these deep

waters were found to be feeding heavily on

squid. Record numbers of squid are now

being caught south of our Sanctuary near

Point Hueneme and the Channel Islands.

Last year, because of El Niño,

salmon fishing within the Sanctuary was

disappointing. The 1999 season, however,

has proven to be a banner year.

Surprisingly, most of the salmon didn't

venture into Monterey Bay itself, but were

found in abundance between Santa Cruz and

the northern boundary of our Sanctuary.

Good fishing was also reported off the

Monterey Peninsula and Carmel Bay. Salmon

this year were of excellent quality,

averaging more than two pounds per fish

heavier than usual.

While sardines remain abundant in

Monterey Bay, their size is somewhat

smaller than usual. The larger sardines

have been found in the northern part of

our Sanctuary, off Half Moon Bay and up to

the waters off British Columbia. The

entire West Coast is witnessing the

re-emergence of this magnificent

resource.

--Dave Danbom

Fishing Industry Representative,

Monterey Bay National Marine

Sanctuary Advisory Council

|

Nearshore

fisheries have existed in California for decades,

but a recent fishery for live fishes used in local

restaurants and shipped overseas started in

southern California in the late 1980s, spread to

northern California in the early 1990s, and now has

become common in central California. These fishing

boats use hook and line, pole fishing, and traps.

Live finfish in California comprise more than 60

percent of the annual nearshore fish landings,

which have increased from approximately 20,000 to

more than a million (M) pounds and from

approximately $20,000 to $2.7 M in value in the

past eight years. Between five and fifty species,

depending upon location, season, and year, are

landed in this fishery.

Recently, the California

Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) created teams to

deal with specific fishery issues. The Nearshore

Fish Team has met several times to discuss how to

evaluate and regulate, if necessary, the live fish

fishery. In its spring 1999 meeting, the team noted

many gaps in knowledge on this fishery and its

target species, including accurate estimates of the

abundance (from both fishery-dependent and

-independent catch and effort data sources),

species composition, natural history, bycatches,

effect of changing ocean conditions, socio-economic

factors, and the ecosystem role of species subject

to fisheries. The team estimated that the costs of

doing the necessary research to fill these gaps

would be approximately $10 M just for the first

year!

Some scientists think the

live fish fishery will fail because it targets

mainly small, immature individuals of shallow,

nearshore fishes. Certainly, fisheries for juvenile

fishes, especially if they target all areas where

these juveniles live, cannot last long. Of special

concern is the fact that many of these fishes are

being harvested before they get a chance to

reproduce for the first time. Since rockfish are

typically long-lived, often take many years to

mature, and are known to have highly-variable,

successful recruitment, harvesting them before they

mature and reproduce can be disastrous for their

populations.

In addition, the live fish

fishery targets sizes and species of fishes not

taken by many fishermen prior to now. Many of these

nearshore fishes are very site-intensive. Thus, any

heavy fishing on their populations—most of which

have established home sites and will not move much

after settling, except to forage and perhaps

reproduce—could be very deleterious to the local

population densities.

In June 1999 the U.C. Sea

Grant Marine Advisory Program and CDFG sponsored a

Workshop on Assessing and Managing Nearshore

Fisheries. Recommendations from fishery biologists

who attended include the need to obtain the best

possible data on catch, effort, species and size

composition, reproduction, maturity, location, site

specificity, larval dispersal and recruitment, and

socio-economic variables to enable CDFG to evaluate

the trends in this increasing fishery and manage it

appropriately.

Two pieces of California

legislation, enacted in 1998, require Fishery

Management Plans (FMPs), shift the nearshore

fishery regulatory authority from the California

Legislature to the Fish and Game Commission, and

establish size limits for selected species. Size

limits between 10-12" were established for six

species of rockfish, including the black and

yellow, gopher, kelp, China, grass, and brown

rockfishes, and limits of 10" for scorpionfish, 12"

for sheephead, and 14" for cabezon. Other species

taken in this fishery include greenlings,

surfperches, deep-water thornyhead fishes, and

crustaceans such as the spot prawn. However, for

most of these species, there have not been

validated age determination or estimates of

age/size at maturity studies. Also, size limits may

not be very effective because many of the

undersized fishes with swim bladders will suffer

barotrauma (disorientation and possible death

caused by pressure change) and not survive well

when returned to the sea.

|

|

|

Pile

surfperch (©Don

Gotshall)

|

Without better information on the life histories

of these species and on the status of their

populations, adequate FMPs will be difficult to

produce. In addition, regulations will continue to

be difficult to enforce due to the transient nature

of the nearshore fish fishery and delivery systems

and the limited enforcement available. More

accurate information on the fishery, habitat

requirements, and life histories of these fishes is

needed to ensure that sufficient management

policies are enacted to guarantee the continued

health of these nearshore fish

assemblages.

--Gregor M.

Cailliet

Moss Landing Marine Laboratories

|

|

Monitoring

Marine Mammal and Seabird Bycatch in the

Monterey Area Set Gillnet

Fishery

|

|

During

the 1980s extensive bycatch of seabirds and marine

mammals in central California's set gillnet

fisheries prompted a series of regulations, which

ultimately appear-ed successful at reducing

mortality of the three species of primary concern:

Common Murre, sea otter (Enhydra lutris) and harbor

porpoise (Phocoena phocoena). A National Marine

Fisheries Service (NMFS) observer program provided

bycatch data from 1990 to 1994, and was

discontinued after 1994 because bycatch of harbor

porpoise was low and no sea otters were observed

entangled after 1990.

In August 1997, however,

an unusual seabird stranding event was detected by

the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary's Beach

COMBERS program (see Bird

Section for program

details). Several hundred dead Common Murres were

found on a 14-km section of beach in southern

Monterey Bay. Because of the localized nature of

the strandings, and because Common Murres had a

history of significant mortality in gillnets,

fishery entanglement was considered a possible

cause of death for these birds.

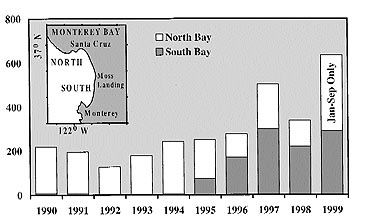

Halibut set gillnet

fishery records revealed that effort had increased

substantially between 1994 and 1998 and had also

shifted to the southern areas of Monterey Bay

(Figure 1). Increasing effort was taking place just

offshore of the beaches exhibiting high seabird

deposition rates. This area historically had high

bycatch rates of harbor porpoise, southern sea

otter, and Common Murres. There was, therefore,

concern over potential increased fishery mortality

for all three species, particularly given an

increase in harbor porpoise stranding rates and an

apparent decline in the sea otter population after

1995 (see article in Endangered

Species section). Without

observer data for 1995-98, however, it was not

possible to estimate accurately the level of

mortality during those years.

|

|

Figure

1: Halibut set gillnet fishery effort for

Monterey Bay in the 1990s.

|

In April 1999 NMFS reinstated an observer program

for the Monterey Bay area set gillnet fishery.

Approximately 25 percent of fishing effort was

observed between April and September, providing

much-needed data on marine mammal and seabird

entanglements. Observed mortalities for this

six-month period included 26 harbor porpoises, 1

unidentified cetacean (almost certainly a harbor

porpoise), 47 harbor seals, 4 elephant seals, 5

California sea lions, 1 southern sea otter, and 286

Common Murres. Although overall mortality estimates

are not yet available, simple extrapolation

indicates that about 100 harbor porpoises, 1,000

Common Murres, and up to 4 sea otters may have died

in Monterey Bay area gillnets during this

period.

Multi-agency efforts are

presently underway to evaluate and address this

mortality. The central California harbor porpoise

population is estimated to be about 5,700 animals,

and under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the

maximum allowable incidental mortality of this

species is forty-two animals per year. NMFS is

therefore currently working with fishermen to

implement voluntary measures to reduce the

mortality of harbor porpoise, including the use of

acoustical devices ('pingers'), which have been

extremely effective at reducing marine mammal

entanglements in other gillnet fisheries. Studies

are also underway to identify the potential impacts

of the present gillnet mortality on southern sea

otters and Common Murres.

--Karin A. Forney

Southwest Fisheries Science Center

|