|

MARINE MAMMALS |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Gray

Whale Calf Census Data* Year Calves Est.

% of total pop. 1999** 400 1.6 1998** 1316 5.1 1997 1439 6.5 1996 1141 5.1 1995 601 2.6 1994 1000 4.5 *Preliminary

results; data gathered from shore-based

sighting surveys of northbound migrating

gray whale calves passing Piedras

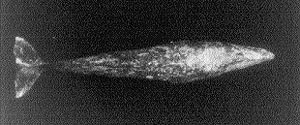

Blancas. There were other anomalous findings concerning this population last year. The southbound migration of gray whales is led by near-term pregnant females, and these "wide-bodied" whales are easily distinguished from other adults (see Figure 1). During late December 1998 and early January 1999, scientists from the National Marine Fisheries Service's Southwest Fisheries Science Center conducting aerial surveys and photogrammetric studies (making measurements from photographs) along the California Bight noted very low numbers of pregnant females swimming southbound. In addition, preliminary analysis of measurements from vertical aerial photographs indicates that whales photographed in 1999 were narrower, relative to their length, than southbound gray whales photographed in 1997 and 1998. These findings suggest that pregnancy rates were lower and overall body condition may have been poorer last year. Figure

1: These horizontal photographs

of migrating gray whales

illustrate how whales change

shape as their condition changes.

The upper image is of a near-term

pregnant female headed

southbound, while the lower image

shows a much thinner northbound

adult. Last year was the sixth consecutive spring that scientists from the Southwest Fisheries Science Center have surveyed northbound gray whale cows and calves at Piedras Blancas, California. Preliminary analysis of those counts shows a dramatic drop in the number of northbound calves (see chart above). Because of the low counts of southbound pregnant females and relatively few reported strandings of neonates, we suspect that the reduction in numbers of northbound calves resulted from a reduction in pregnancy rates rather than an increase in calf mortality. The combination of observations for 1998–1999 clearly indicates that last year was not a good one for gray whales. We don't know whether the changes we report are the result of a short-term shift in their environment or whether they reflect the first signal of a long-term change in this population. There have been reports from scientists studying the benthic amphipods—the gray whale's primary prey in the northern Bering Sea—that these populations of small crustaceans may be less abundant than they were a decade ago. The 2000 migration may provide the answer to many of these questions. --Wayne Perryman Elephant

Seal Populations 1997 1998 1999

Año

Nuevo Births1 2684 2797 2362

High

count2 5358 4588

Other

Big SurBeaches Pups to

weaning3 500 120 420

Piedras

Blancas Births4 1200 1650 1900 High

count5 5000 5000 4000 Sources: Elephant

seals haul out on beaches along

Sanctuary shores at various times

during the year. (Kip Evans

© MBNMS) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Home | Introduction | Visitors | Education | Research | Protection | Calendar | Foundation | Search

Credits

For comments or question please refer to the Webmaster

Last modified on: March 31,

2000